The Hidden Death in the Victorian Wallpaper

Arsenic was a hidden killer in Victorian homes, but it also played a large part in the British economy. Which comes first: commerce or public health?

When it opened in 1881 the comic opera Patience was the first theatrical production in the world to be lit entirely by electricity. But the librettist, W.S. Gilbert, was no fan of scientific fashions. One of his satirical targets was William Morris, the textile designer who advertised the must-have colour of the century: a vivid green originally produced in a Swedish laboratory. After a long series of mysterious illnesses in Britain’s most fashionable homes – even Queen Victoria’s Osborne House was not immune – Morris’ vivid wallpapers had been denounced as arsenic-packed killers. As the years went by, Morris desperately tried to distance himself from the scandal. ‘Do not fall into the trap of dingy, bilious yellowy-green’, he warned, claiming that he felt ‘a special and personal hatred, because I have somewhat brought it into vogue. I assure you I am not really responsible for it.’ Or in Gilbert’s sarcastic parody: ‘I do not care for dirty greens/By any means.’

Nine of Morris’ first 11 designs, produced from the 1860s, included arsenic, but at the time he repeatedly denied culpability, condemning what he called ‘the arsenic scare’ as a lazy fabrication by doctors incapable of diagnosing their patients properly. In his view, the inexplicable outbreaks of disease should be attributed ‘to the water closet, which I believe to be the source of all illness’. Although that verdict might sound a lamentably laughable excuse, it did have some justification. So was Morris a corrupt hypocrite, a Victorian capitalist set on ruthlessly maximising his profits? Or was he simply old-fashioned and misguided, vainly trying to smooth over some unfortunate mishaps?

Miasmas

Florence Nightingale saved thousands of soldiers’ lives by introducing basic hygiene measures, yet she refused to accept the existence of germs. Instead, she adhered to the traditional belief that disease is caused by clouds of bad gases known as miasmas, such as the poisonous stenches emitted from rotting food or marshes. Miasma theory had lasted for centuries, and there was plenty of evidence that apparently supported it. For example, recurrent cholera epidemics raged most fiercely in filthy slums, and even after 1854, when John Snow traced a Soho outbreak to the water supply, miasma supporters continued to oppose sanitation reforms.

The most virulent debates were in London, where the quality of the Thames had been deteriorating for decades. The river’s colour and odour provided daily reminders that the city was literally overflowing as raw sewage and industrial effluent seeped into the water to be deposited in thick layers on the banks. London’s medieval drainage system was no longer able to cope with the ever-expanding population. Streams that had formerly carried sewage away were being covered over by housing developments, while cesspools were often left unemptied because of rising labour costs.

The situation deteriorated still further when a well-intentioned reformer, Edwin Chadwick, recommended that overcrowded slums could be protected by discharging their cesspools directly into the Thames. And then there was Morris’ culprit: the water-closet. Despite their advantages, flushing toilets – often shared by multiple households – generally discharged straight into the river. In addition, unsophisticated plumbing technology meant that foul-smelling toxic fumes could travel up the pipes and into the surrounding air.

In 1828 a Royal Commission had agreed that something needed to be done. Yet although the government set up committees, it failed to make any decisions until 1858, the summer of the Great Stink, when temperatures soared, water levels dropped, and Benjamin Disraeli fled from the House of Commons debating chamber near the Thames when the smell became unbearable. At last, action was taken. Within only a few weeks, new laws were passed and vast amounts of money were borrowed to construct the Victoria Embankment and the underground network of sewers that is still in operation today. But even after sewage was being swept far away in massive tunnels, water companies built tall chimneys to release sewer gas high up in the atmosphere. For miasma proponents like Morris, these noxious clouds could be blamed as the source of health problems.

Laced with arsenic

Arsenic green, warned a Punch journalist, was ‘the hue of death, the tint of the grave’. But he spoke out too late: from the beginning of the 19th century this cheap pigment added lurid vibrancy to sweets, paper, clothes, paint, and other household items. Artificial flowers were particularly popular, produced by hundreds of underpaid workers – some as young as eight – who spent up to 16 hours a day dyeing muslin leaves. Doctors attributed the countless cases of skin sores, stomach pains, and vomiting to atmospheric ‘devil’s dust’ floating round the workshops, but no action was taken until 1861, when a flower maker died in agony.

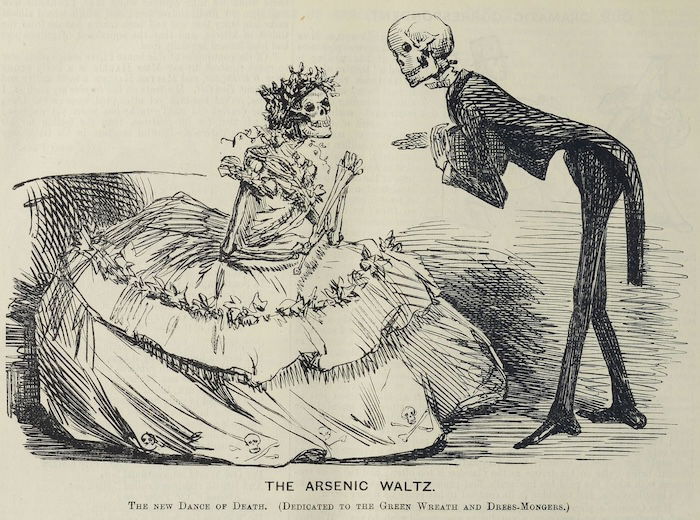

Her gruesome symptoms were detailed with relish in the press. A macabre caricature in Punch showed a skeletal couple embarking on a fatal waltz, and crinolines were condemned as dancing carriers of death for male chaperones whose ‘fair charmers in green whirl through the giddy waltz … in a cloud of arsenical dust’. But men were threatened long before they ventured on the ballroom floor: their socks, hair bands, and paper collars also contained arsenic-based substances, to say nothing of hair pomades, cigar holders, and playing cards.

As Gilbert highlighted, technological advances can introduce risks as well as advantages. By the middle of the 19th century innovations such as steam printing and large-scale paper production meant that wallpaper was now far more affordable. And after oil and gas replaced candles, their stronger light meant that darker shades could be used. As green became ever more popular, many thousands of homes were smartly decorated with chemical papers and fabrics. Patients complained to their doctors about feeling tired, or headachy, or nauseous, or sore-eyed – vague and varied symptoms that defied diagnosis. In women, such signs were often attributed to the convenient catch-all of nervous problems. Sufferers were confined to bed with the windows closed, surrounded by arsenic-infused walls, curtains, and bedcovers.

Although initially mystified, doctors carried out systematic studies to confirm a correlation between redecoration and the onset of illness. But just as happened a century later with smokers and cancer, arsenic-deniers fell back on the limitations of such statistical evidence: perhaps it was just chance, they argued, that patients recovered when the walls were stripped. In any case, the chemical was not universally condemned: some medical experts recommended smoking arsenical cigarettes to reduce nervous spasms, while Fowler’s arsenical fever medicine was still being listed in the 1970s. The exact mechanism of arsenic poisoning was hard to pin down: symptoms varied and not everybody was affected in the same way. Another difficulty was explaining how the arsenic got off the wall and into people’s bodies. It was only in the 20th century that a specific chemical was identified, a lethal gas released from wallpaper by fungi or under damp conditions.

While the government dithered, manufacturers yielded to public protests and stopped using synthetic dyes. The case against arsenic may not have been definitively proven, but consumers were refusing to buy questionable products.

A toxic industry

Again and again, juries and public health officials were reluctant to press for government legislation. While other European countries imposed restrictions to safeguard their citizens’ health, many people in Britain hid behind the mantra of freedom to protect the commercial interests of industrialists. Of course it was unfortunate if a child died, but that was – they argued– simply a regrettable consequence of being free to buy the product of choice.

Morris publicly protested against cheap, synthetic dyes, becoming a leading campaigner for reviving traditional pigments – yet his company did not finally eliminate arsenic from its products until 1883. He had a vested interest in these debates: his wealth stemmed from his father’s lucrative mining venture in the West Country, and at one stage he was a major shareholder in the company producing half the world’s arsenic.

In 1864 a landmark enquiry exposed the atrocious working conditions in his family’s copper mines, yet four years later Morris wrote ‘The God of the Poor’, which features a mighty lord who ‘On poor folk trod he like the dirt/None but God might do him hurt.’ He subsequently became a director of Devon Great Consols, which manufactured arsenic from low-grade copper ore. Eventually the Home Office set up an official investigation into arsenic production, discovering that the workers wore little protective clothing and often died from lung disease, but the report was never published: arsenic played too large a role in the British economy.

Shortly before he died, Morris remarked that his family ‘had some mining shares in Cornwall, and when I succeeded to them I sold them’. He did not reveal that this sales process lasted 22 years. Morris seems to have been a more complex, troubled person than the familiar Arts and Crafts hero we remember today.

Patricia Fara is an Emeritus Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge.